Anti-Feminist Archetypes in Film

While the evolution of film narratives alongside feminist ideology has allowed strong, independent women to flourish in fiction, many cult classics are guilty of portraying anti-feminist characters. First, I have to establish what I mean when I say “anti-feminist character”, because I’m not referring to a woman who expressly advocates against women’s rights – the issue is slightly more subtle and much more nuanced than that. The anti-feminist character tends to be a woman who is regarded as a feminist icon in some respect, while fundamentally opposing feminist beliefs in a myriad of ways. Since anti-feminist characters can be conceptualized so variedly, I’m going to present you with a few archetypes, based on characters from cult classics, in order to better illustrate this concept. Notably, each of these archetypes has been given a title that conveys the anti-feminist principles it projects.

*I will be discussing characters from The Devil Wears Prada, Legally Blonde, Mean Girls, and Maleficent, so proceed with caution of spoilers.

The gaslight, gatekeep, girlboss archetype: Miranda Priestly

While I’m not entirely sure whether or not The Devil Wears Prada (2006) is considered a cult classic, it’s certainly referenced in pop culture rather frequently. This film presents what I’ve deemed the gaslight, gatekeep, girlboss archetype through Miranda Priestly: a woman in a position of power who is depicted as manipulative, mean, egocentric, and who contrasts traditional nuclear family values. Miranda is problematic in so many ways: she betrays people in order to maintain her power, she constantly makes malicious comments about people’s appearances (and is incredibly fatphobic), and she manipulates those around her to serve her personal interests. This archetype presents a woman who is essentially void of morality as a mechanism to climb the hierarchical ladder of her chosen profession. A significant aspect of Miranda’s storyline, in relation to this archetype, is the perceived failure of her family life, as she confides in Andy that she is getting another divorce. While this is the first time in the film that Miranda is portrayed as genuinely emotional, she seems most concerned about the repercussions of her divorce relating to her public image and how it will impact her career (which furthers the conception that she is egocentric). The inherent harm of this archetype is that it enforces the notion that women cannot have it all, meaning that they cannot have a successful career and marriage without either being corrupt/ becoming corrupted in the process of trying to attain success or without losing one of those things while striving for career advancement. This is further enforced when Miranda tells Andy that she parallels her, in terms of her career aspirations and what she’s willing to do or who she’s willing to sacrifice to get ahead. Andy rejects this notion and abandons her prestigious position to find another job – one where she isn’t expected to make significant sacrifices, making Miranda both the antagonist of the story and a foil to Andy’s character.

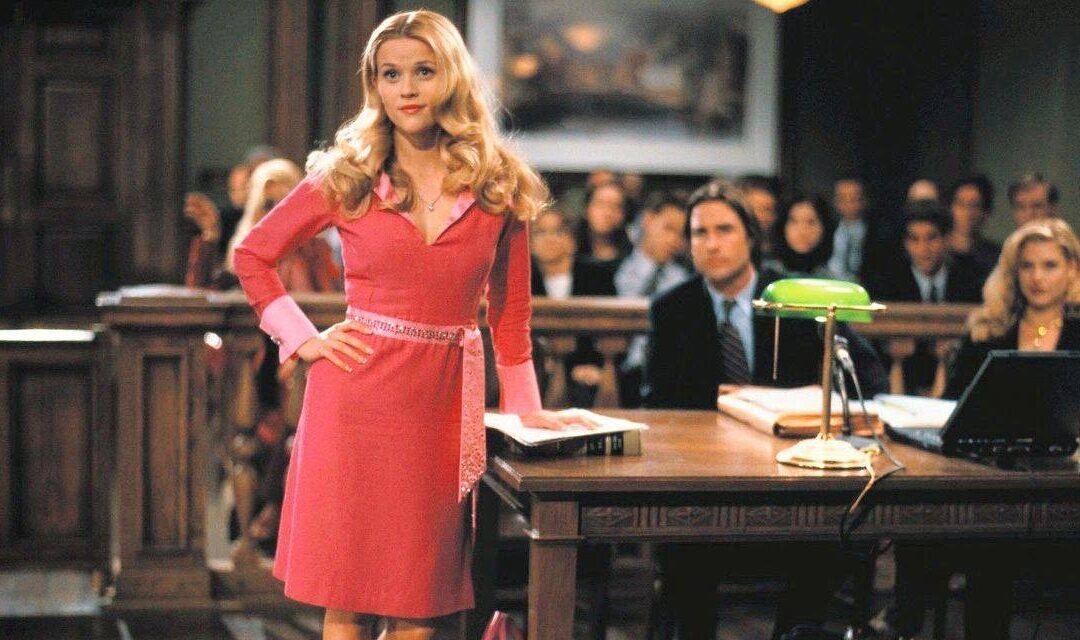

The boy-crazy girlboss archetype: Elle Woods

Now don’t get me wrong, I loved Legally Blonde (2001), but Elle Woods is a perpetuator of an anti-feminist narrative for the majority of the first film (apparently Legally Blonde will become a trilogy in 2022???). Her entire motive in going to Harvard Law School is to win her ex-boyfriend back. The boy-crazy girlboss archetype is thus primarily driven to attain a specific, generally career-oriented, goal because of a man. In Elle’s case, the driving motivation in her application to Harvard is that she will be able to present a version of herself to Warner that fits his ideals for a wife. Thus, her desire to go to law school and her drive to succeed is entirely dependent on the hopes that this will lead to the fulfillment of her romantic desires (i.e., Warner realizing that she’s the gal for him and taking her back) and is not initially dependent on her genuine desire to become a lawyer. While this film certainly does a good job of highlighting gender inequality within the spheres of academia and the legal profession, the protagonist is not depicted as autonomous and independent from men. Although her motivations eventually shift throughout the film (she eventually realizes she doesn’t want to win Warner back since he’s literally the worst), the centrality of her character is initially her focus on romantic fulfillment through acceptance to a prestigious academic institution. Thus, while Elle eventually learns how to be independent and pursues a career in law for herself, it is significant to note that her romantic goals acted as a catalyst for her initial pursuit of success.

The personified glass ceiling archetype: Regina George

Mean Girls has acquired a massive cult following, and presents a variety of archetypes, but first, I want to focus on Regina George. Regina George illustrates the personified glass ceiling archetype. This archetype is fittingly named because it presents a woman who takes on the purpose of the metaphorical glass ceiling: an invisible barrier that prevents others (in this instance, specifically referring to women) from rising above a certain level in a given hierarchy. Regina George establishes herself at the top of the social hierarchy and seeks to maintain her elevated status by stopping other women from socially ‘surpassing’ her. In order to do this, she manipulates and sabotages others so that she can maintain domination of the social hierarchy. This archetype is problematic because it promotes the idea that women are in competition with one another for success, and that there is limited space at the top of the social hierarchy. This opposes feminist ideals of celebrating other women without perceiving their successes, achievements, or statuses as threats to the potential of your own.

The vengeful shrew archetype: Janis Ian and Maleficent

While Janis Ian is, in some ways, a distorted, mirrored version of Regina George (both of them are assertive women who are driven by anger, jealousy, and resentment), she presents her own unique set of problematic qualities. While the personified glass ceiling archetype seeks to monopolize the peak of the social hierarchy, the vengeful shrew seeks to shatter the ceiling, not for personal gain, but for revenge! This desire for destruction is generally attributed to direct victimization from the former – establishing a sort of villain-origin story. In Mean Girls, Regina George rendered Janis Ian into a social outcast, thus preventing her from climbing the social hierarchy and confining her to the bottom of the ladder, by outing her as a lesbian (which, as it turns out, is not true and she is Lebanese – so the entire rumour was based on miscommunication – but that’s another point of discussion entirely). The vengeful shrew thus justifies any actions indicative of moral corruption because she deems them to be reparations for negatively impactful actions taken against her by the personified glass ceiling. These archetypes thus generally exist in tandem, but not exclusively.

Maleficent presents a version of the same archetype, but one that is not dependent on the existence of the personified glass ceiling within the same narrative. Maleficent’s version of the vengeful shrew is a character whose villain-origin story is a product of a broken-heart. Her anguish leads her to commit multiple atrocities for the sake of revenge. The narrative of this film seeks to make the audience sympathize with her, thus justifying her actions and allowing her to be redeemed by conceptualizing her character as fundamentally good, but damaged. In reality, her misdeeds are a product of her inability to process emotions in a healthy way and move on. Despite her eventual redemption, this archetype is problematic for multiple reasons: (1) it enforces the notion that women are irrational and incapable of dealing with their emotions in healthy ways, (2) it justifies corrupt and harmful behaviours born out of grief for the sake of revenge, and (3) it presents yet another strong, female character who is morally corrupt.

These archetypes are harmful because they either enforce the notion that women are fundamentally incapable of balancing successful careers and successful relationships, they portray the desires of women as dependent on the desires of men, they pit women against one another, or they depict women as irrationally emotional. While my intention is not to speak ill of these films, I do want to highlight the problematic nature of certain female character archetypes, and how they infringe on feminist ideals. It’s also important to consider the role of a potential anti-feminist character within a film, as the ones I have outlined vary in terms of being protagonists or antagonists. While an antagonist is expected to be problematic in multiple ways, I would love to see the portrayal of a female antagonist whose negative qualities aren’t based on misconceptions and stereotypes surrounding womanhood. In terms of protagonists, I would be overjoyed to never again be subjected to the trope of a woman’s successes and desires being dependent on a man. Frankly, I’m pretty tired of seeing portrayals of women that lack depth and are centred on anti-feminist stereotypes. While I’ve presented you with three anti-feminist archetypes, this list is certainly not exhaustive. When engaging with films, I challenge you to be conscious of the potentially harmful, anti-feminist archetypes it depicts.