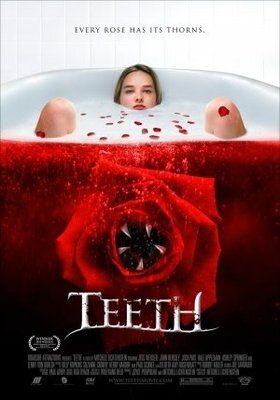

Guard Dogs at the Gate: The Subversive Empowerment of Teeth

TW: this article contains mentions of sexual assault and violence

If I looked into your eyes and told you that this particular horror film was about a woman with teeth in her vagina, you might laugh. You might scoff, nod, or ask where it’s streaming. Three years ago, when my friend and I discovered that Teeth was available on Netflix, my response was to do all four. At three in the morning, sitting on her sofa-bed hybrid in lower Manhattan, we listened to the familiar thump of the Netflix introduction and felt a mix of fear and curiosity about the 1.5 hour journey ahead of us. Though I covered my eyes for most of the film, I have since returned to examine the debate it sparked. After combing through a bottomless hole of wordy blogs which shrewdly discuss the relative feminism, faux-feminism, phallic power dynamics, and psychoanalytic implications of Teeth, I have derived both an intense headache and strong opinion about a film that I was barely able to sit through.

Teeth features Dawn O’Keefe, a doe-eyed teenage spokesperson for a Christian abstinence group called the Promise. During her time with the Promise, Dawn meets Tobey, a purported fellow believer in post-espousal virginity loss. In the first of the film’s four or five gory revenge vignettes, Tobey loses half of his penis to Dawn’s teeth, after he attempts to violently rape her. His assault is how Dawn discovers her unique condition: vagina dentata, a toothy defense mechanism built into her vagina to ward off nonconsensual advances and abuses.

Produced during the presidency of George W. Bush, Teeth was birthed against a backdrop of censorious misogyny and restricted sexual autonomy. As a clear rebuff to male hegemony, Teeth subverts oppressive notions of women’s chastity and virginal “purity.” While Dawn’s reclamation of her body symbolizes teenage self discovery, it also confiscates the weaponized masculinity of the men who try to rape her (these “weapons” being their penises). At the film’s conclusion, when Dawn gets into a car with a lecherous older man, she smiles, unfazed by his very apparent intention to abuse her. This affirms her control over her body’s defense, as well as the film’s designation of men as invariable, faceless, and conquerable. Rather than vagina dentata transforming our heroine into a monster worthy of classic horror, her condition safeguards her against the real monster: a male world which seeks to simultaneously limit and possess her sexual self perception. The misogynistic social undercurrent of a woman’s role as sexual gatekeeper is turned on its head: Dawn emerges as gatekeeper, only with dental guard dogs at the gate. In Teeth, the beasts are men and Dawn is the superhero sent from Krypton (or “Tooth-ton”) to stop them.

In Teeth’s production, as well as the public response it inspired, a notable lack of understanding surrounds the film’s intention. In an interview with Vice, director Lichtenstein discusses how Teeth’s distribution company misguidedly marketed the film to an audience of purist horror fans. The trailer, for example, exhibits none of the wit or satire that the role of Dawn brings to the film. Fadeouts and fade-ins of a sinister gynecology appointment lead viewers to believe that Teeth is just another porno-slasher in which women are objectified, expendable, or evil, rather than agents of their own supernatural mutations. The Vice article quotes the following lines of Jim Emerson’s review of Teeth as yet another example of a double standard response to the film’s graphic scenes:

“When Dawn’s first full-frontal victim looks down to find he’s not even half the man he used to be, he seems genuinely hurt-- by the rejection as much as the castration. In a bloody, nightmarish, young-romantic way, it's kind of touching.”

Emerson not only misses the entire point of the film, but attributes the part of “survivor” to Tobey rather than Dawn. Instead of viewing the scene for what it is, a violent attempted rape, Emerson myopically reads it as a bloodily embellished, awkward romantic rejection. The failure of certain audiences to grasp Teeth’s meaning is almost as satirical as the film itself.

As producer Joyce Pierpoline argues, the worst kind of reaction elicited in a moviegoing audience is one of indifference. Whether it’s considered a cultish, Carrie-esque satirical horror, a tale of feminist revenge or a sad excuse for a movie, Teeth most definitely inspired a visceral response. Any criticisms or commendations of cinematography and soundtrack pale in comparison to the film’s foundational concept. Because of this, rather than arguing the movie’s relative merit, I will venture to say that Teeth is important. Psychological assessments of Dawn’s personal autonomy aside, Teeth stands as a revealing commentary on how imposed standards of intimacy (or lack thereof) sustain the rape culture that pervades real society.